While I wasn’t looking last week, a Peak District autumn that seemed like it would last forever – livid trees and hard ground – turned into steely, slippery November, rain on the pavements and mist over the flats of Sheffield. I’m waiting out the last few weeks of pregnancy, a strange limbo where I feel alternately exhausted, excited, weepy and calm, where I want to swim determined lengths in the pool feeling the baby kick under me or lie on the sofa reading things that might shock me into new feeling, take me out of my reverie.

While I wasn’t looking last week, a Peak District autumn that seemed like it would last forever – livid trees and hard ground – turned into steely, slippery November, rain on the pavements and mist over the flats of Sheffield. I’m waiting out the last few weeks of pregnancy, a strange limbo where I feel alternately exhausted, excited, weepy and calm, where I want to swim determined lengths in the pool feeling the baby kick under me or lie on the sofa reading things that might shock me into new feeling, take me out of my reverie.

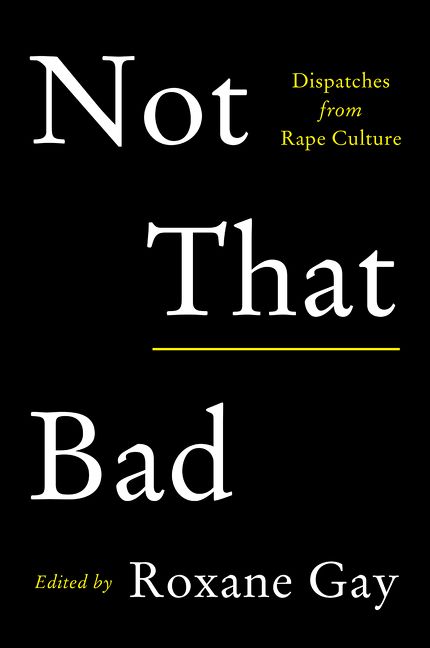

One of the books I’ve gravitated towards is ‘Not That Bad: Dispatches from Rape Culture’ edited by Roxanne Gay. At a time when I’m emotionally vulnerable (I can’t bear sad or violent films) it might seem like a strange choice. But I AM very glad I chose it, because late pregnancy is also a time to think about what it means to be a woman, and being a woman means having to think about the pervasiveness of rape culture.

Beginning with a brilliant, incendiary introduction from Gay (‘if rape culture had its own cuisine, it would be all this shit you have to swallow. If rape culture had a downtown it would smell like Axe body spray and that perfume you put on tampons to make your vagina smell like laundry detergent…’) the essays centre around experiences of assault and the climate behind it, interrogating what it means to live in constant fear of harassment and aggression. They’re impressively wide-ranging, considering everything from the rape epidemic embedded in the refugee crisis to accounts of street harassment and the fear of walking home at night. It contains accounts from men and trans women, women from many different backgrounds, all writing eloquently and bravely about stories which need urgent telling. I found every piece surprising – a fresh shock, a jolt to the system – and yet depressingly familiar too. They deal with the problems of guilt attached to assault and survival. As Claire Schwartz writes: ‘”You’re so lucky you weren’t killed,” the first person I tell tells me…’. As Stacey May Fowles puts it, connecting back to the title of the book:

Beginning with a brilliant, incendiary introduction from Gay (‘if rape culture had its own cuisine, it would be all this shit you have to swallow. If rape culture had a downtown it would smell like Axe body spray and that perfume you put on tampons to make your vagina smell like laundry detergent…’) the essays centre around experiences of assault and the climate behind it, interrogating what it means to live in constant fear of harassment and aggression. They’re impressively wide-ranging, considering everything from the rape epidemic embedded in the refugee crisis to accounts of street harassment and the fear of walking home at night. It contains accounts from men and trans women, women from many different backgrounds, all writing eloquently and bravely about stories which need urgent telling. I found every piece surprising – a fresh shock, a jolt to the system – and yet depressingly familiar too. They deal with the problems of guilt attached to assault and survival. As Claire Schwartz writes: ‘”You’re so lucky you weren’t killed,” the first person I tell tells me…’. As Stacey May Fowles puts it, connecting back to the title of the book:

“There is this impossible paradox when you are a victimised by sexual assault. You want to – you have to – convince yourself that it wasn’t “that bad” in order to have any hope of healing…. on the other hand, you need to convince others it was “bad enough” to get the help and support you need to do that healing. To get out from under it…. You tell yourself how bad it is and then you numb yourself to how bad it is.”

Zoë Medeiros’ piece ‘Why I Stopped’ had a particular impact on me – an account of why she no longer tells anyone about the trauma she experienced:

“It did not help me to tell. I felt a momentary burst of clarity, like walking out into a cold night and feeling that icy slab of air hit my face, and then I felt gutted every single time.”

This too is the paradox of surviving sexual assault: the urge to share the story (to be ‘seen’ in doing so) and the fear of doing so, fear that is often grounded in the reality of people’s confused and confusing reactions. Doing this is writing (whether through essay, journalism, fiction or poetry) can feel no less exposing than talking to another person. And the paradoxes so many of the essayists in ‘Not That Bad’ describe connect to a more fundamental dilemma of subjectivity, the way women learn to experience their bodies through culture. The first piece in the book by Aubrey Hirsch is called ‘Fragments’ and expresses this brilliantly:

“You recognise the tension between “I am a body” ands “I have a body,” but you are unable to resolve it. “Have” implies that this body is just a possession, that it can be lost and thrown away. That you can do without it. It implies, perhaps, that someone else could have your body and that your body would be not your own. That it would belong to another.

That doesn’t feel quite right.

But “am” doesn’t seem right either. To “be” a body suggests that you are only a body. You are meat and some blood. You are hard bones and flexing cartilage. You are tangled veins and skin. Is that all, though?”

As I try to live in this liminal space anticipating motherhood, the tension between having and being a body is foremost in my mind. To have, to be, to occupy, to experience a female body and its subjectivity is to navigate the complexities ‘Not That Bad’ documents through essays. The whole book should be required reading for men starting university everywhere and more widely, for fathers and partners and brothers and teachers. And if not the whole book, then perhaps the final essay by Elissa Bassist, ‘Why I Didn’t Say No’ which I’m taking this extract from:

“Because love rewards the optimistic and punishes those who vocalise their fury. At first we had sex despite my pain; months later, we still did – because women are bred for pain, for giving birth when birth splits us open. Because we learn to live with it; because we learn to live for it. Sontag again: “It is not love which we overvalue but suffering.” Because rom-coms train us that if we suffer enough, then everything works out.”